With finals approaching, two main problems with traditional grading have become more apparent in humanities courses. In these courses, grades are more subjective and cannot be defined with merely A’s, B’s, and C’s.

“In English, [grading] will always be a problem, because the nature of reading and writing and thinking is so abstract and complex,” English teacher Christina Serkowski said. “Even the way we teach the same book or the same project, each of us brings our individual personality and unique own human perspective to it.”

To reduce bias in grading, teachers try various methods. In the history department, multiple teachers may occasionally look at students’ assignments to standardize grading.

“Sometimes, there will be a grading norm process where, for example, three teachers on the ninth-grade teaching team might get together and look at one e

say from a student,” history department head Andrew Schneider said. “They would all read it and talk about how they assessed it to try to standardize grading.”

Teachers in the English department try to compare and grade essays anonymously, meaning that the teacher does not know which student wrote the essay.

“What we try and do in the English department is to compare essays from our students with each other and grade them anonymously,” English teacher Carl Fau

cher said. “So that we do our best to have this same understanding.”

Schneider believes grading anonymously is problematic as teachers are usually able to identify a student’s writing because of prior conferences with said student.

“An essay might go through a couple of stages of revision where you couldn’t take the student’s name off of it, but I know who [wrote] it because I’ve worked with that student through the process,” Schneider said.

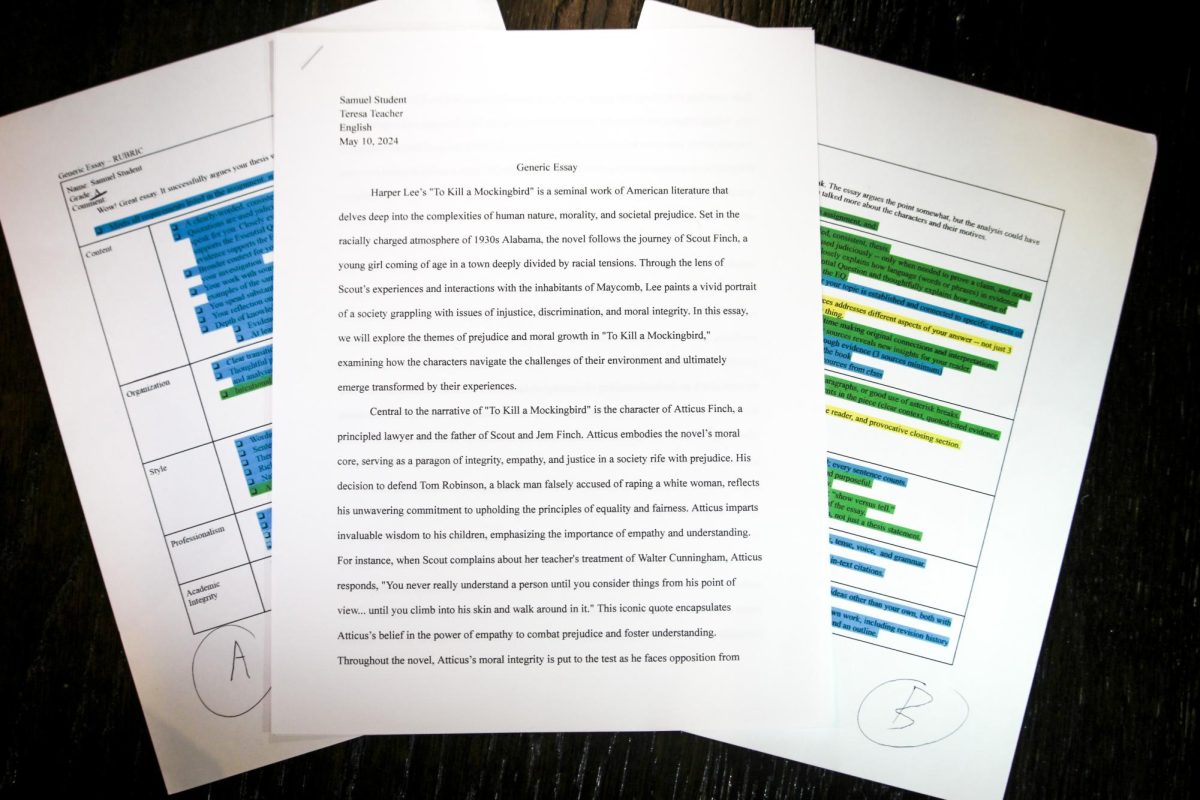

Both Faucher and Serkowski express reservations toward using rubrics in the English department. Faucher prefers grading in narrative form, in which he can outline a student’s strengths and weaknesses; however, time constraints prevent him from doing so.

“Ideally

, our feedback should be all narrative informative, so that students are getting a full picture of their strengths and challenges,” Faucher said. “We don’t work in a system where we have the flexibility or the time to do that. We’re expected to turn in a grade at the end of the semester.”

Serkowski believes that rubrics reduce original thinking.

“Students are often focused on what they need to do to get an A,” Serkowski said. “So when they get a rubric, they see it like a checklist. In addition to that checklist being a creativity-killer, students get lost in the details.”

Instead of rubrics, Serkowski has tried grading based on competencies instead of using traditional point systems.

“I have tried to shift my grading toward competency-based assessment… so a student can perhaps see more clearly what skills they need to work on,” Serkowski said. “I use descriptors to provide feedback instead of letter grades, such as ‘proficient’ and ‘competent’… [and] I’m using a spectrum to help students see that demonstration of these skills happens on a spectrum – nothing we do is quantifiable”

To make grading more fair among different teachers, Schneider believes it all comes down to experience.

“It does help when teachers have more experience teaching and grading essays because they can draw on a greater wealth of experience in terms of what makes student essays successful or unsuccessful,” Schneider said.

Faucher suggests that one method for more straightforward grading is for teachers in the same department to communicate more with each other about standards.

“The more time we spend with each other to have these conversations, the more aligned we are with our grading,” Faucher said. “The more time we can spend with each other, having these conversations, the better it is for the kids.”

Another option could be to get rid of letter grades altogether.

“I wouldn’t give letter grades,” Serkowski said “Kids have to read a lot and write a lot as they develop thinking skills and voice, and every kid develops at their own pace.”