Three hours, hundreds of bubbles, and the clock ticking quickly forward; standardized testing is a dark shadow that looms over every junior and senior. With it comes the anxiety of going into overdrive studying and preparing. For most students, the challenges of the SAT and ACT are the main hurdles they must overcome to finish high school. For others, it’s much more complicated.

Learning and Testing Specialist Julie Smith is one of the school’s

accommodations coordinators for students applying to take standardized tests. Additionally, she is one of three case managers for students who need specified plans for extra support in their learning, otherwise known as individualized learning plans. After more than five years at University Prep, Smith’s process to help students get SAT and ACT accommodations has not changed.

“I have to start my process really early to get everything in place,” Smith said.

Smith starts having conversations with 10th grade families in January to prepare for their standardized testing the following year.

“I have to have enough time to make sure all of the paperwork is in order,” Smith said. “So it is a long process.”

Even with a plan in place, students can still run into difficulties. Senior Alexa Carlisle, who was diagnosed with dyslexia and dysgraphia in second grade, received her ILP once she enrolled in UPrep during sixth grade. Her accommodations, she felt, ran smoothly until her junior year when the College Board required her to get a reassessment of her diagnosis before taking the SAT. According to Carlisle, her doctor concluded in the evaluation that she no longer needed accommodations because she was effectively combating the symptoms.

“It just felt harmful to me because dyslexia and dysgraphia have been a big part of my school life and my identity for a long time,” Carlisle said. “For them to just swoop in and take this one super simple test, that was like 30 minutes long, that I should pass with flying colors and then be like, ‘Oh, you’re good. This no longer affects you.’ It just felt like it was taking a massive part of my identity, who I was, and flushed it down the drain.”

As a result, Carlisle said the College Board rejected her request for accommodations and the school removed her ILP. The Integrated Learning Office is unable to discuss individual students, but according to Smith, what Carlisle describes is an uncommon sequence of events.

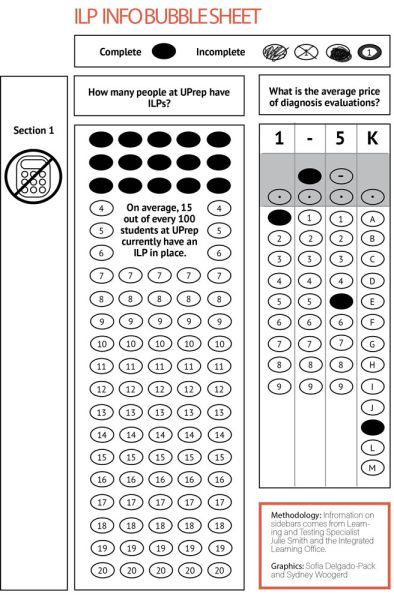

Even before getting accommodations for standardized testing, a student must first have an established ILP which they get after a diagnosis. The diagnosis evaluation itself can take anywhere from two to three days over the course of many sessions and must be completed by a licensed educational psychologist or neurophysiologist.

Dr. Elizabeth MacKenzie has been in private practice diagnosing students with learning disabilities for 20 years. Since graduating from university in 1997, she has been unhappy with the steady increase in difficulty for students trying to get diagnoses, which has only worsened since COVID-19.

“That’s the hardest thing: limited access. Limited access to insurance reimbursement, limited access to providers,” MacKenzie said. “I see third graders who can’t read, and it’s painful to see that.”

MacKenzie charges $3500 per student diagnosis evaluation, and her waitlist is six months long. Despite the benefits of the subsequent ILP, some families mi

ght not have the money or time to get one.

For Steve Chavez, parent to sophomore Andy Chavez, Andy’s $2000 diagnosis was paid for completely out of pocket and took about three months.

“Time is a big issue,” Steve Chavez said. “I think that we were quoted from some folks that it was going to take six months to a year just to get the testing done, but we were very fortunate.”

According to the Executive Director of Special Education at Seattle Public Schools, Devin Gurley, all public schools in Seattle provide free evaluations under the Individuals with Disabilities Education Act, established in 1975. The district will provide any student eligible with an evaluation and will

assist them in creating an individualized education program free of cost. UPrep only provides services after an outsourced

diagnosis. Additionally, Seattle Public School students do not need an official medical diagnosis to receive accommodations just a district evaluation.

As a seventh-grader in public school, Andy Chavez was diagnosed with ADHD by a medical professional. When he came to UPrep in eighth grade, the school advised his family to get a wider-ranging evaluation to see if he qualified for an ILP. Reflecting on his second evaluation, Andy Chavez wished the process went differently.

“I think that the school should make individual learning plans more

accessible,” Andy Chavez said. “It’s really expensive to even get one…it’s kind of dumb.”

Associate Director of Admission and Financial Aid Doug Moon has worked at the school for three years. In his time at UPrep, he has never been able to provide financial aid for families interested in getting a formal diagnosis.

“We’re still working on that,” Moon said.

He added that he does not have the budget to fund students at their financial aid percentage but is looking to create a new system.

“I was thinking of a scale: so if you receive aid between zero and 50%, here’s what we will discount you at,” Moon said. “So that’s the idea moving forward with evaluations in particular.”

Once a diagnosis is complete, formalized, and submitted to the school, Smith can continue with the student and their family to create an established learning plan based on the evaluator’s recommendations. After that, Smith works with students on self-advocacy skills.

Despite the support UPrep provides, challenges can still persist in the classroom. Throughout high school, Andy Chavez has had conflicts with teachers about using his ILP.

“Teachers would say that they thought that I didn’t need it because I was, too smart to need it and they thought that I could just push through and not need an extension or other accommodations,” Andy Chavez said. “One time, I spoke back, and the teacher still refused. My individual lear

ning teacher had to basically argue with the teacher for a week to get them to let me use accommodations.”

In the midst of these challenges, a huge resource that helped Andy Chavez was the Integrated Learning Office. He said it is a calm, productive environment with faculty who help support students in their learning.

“A lot of students don’t know about it either. They think that if they aren’t diagnosed with ADHD or something then they can’t ask for help,” Andy Chavez said. “They’ll help you. Even if you aren’t diagnosed with anything, they can help you plan out projects and everything.”