Swapped Identities

POC students are often confused for one another in class

Photo: Mira Hinkel

Freshmen Huda Hassan and Umu Abdilahi and Senior Juweriya Abdilahi pose for a photo. Edited together, they represent the singular identity they are often reduced down to.

Students of color find themselves reconsidering relationships with peers and teachers when mistaken for others on the basis of race and ethnicity, whether that’s being called by the name of another or being marked absent from classes in which they were present.

Freshman Huda Hassan remembers a time in eighth grade where a peer repeatedly mistook her for her friend Umulkhayr.

“She’s tall, she’s light skinned. I’m short, I have a darker complexion,” Hassan said. “So we were playing, you know, a game with our PE class and someone that we’ve known since sixth grade had called me Umu multiple times during that game…so I kind of like stopped playing and went up to them and was like, stop calling me Umu, I’m Huda.”

As a new semester begins and teachers welcome new students to their classes, freshman Aslan Malik has noticed that this happens more frequently.

“It happens a lot during the beginning of the semester, obviously, because that’s when teachers are most unfamiliar [with their students],” Malik said. “We’re just being classified as one thing and you can’t really differentiate that but you can differentiate like, the millions of white students.”

This can be especially isolating when many students feel like it happens less frequently to their white peers.

“I don’t see any other like, blonde, blue-eyed, other pale kids getting called the same name as another,” Hassan said.

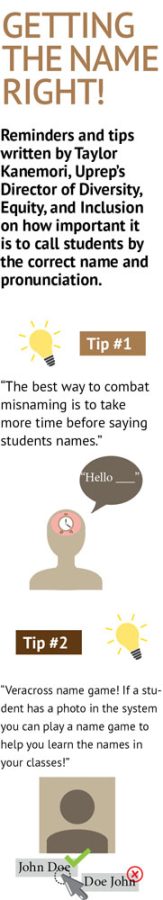

Director of Diversity, Equity, and Inclusion Taylor Kanemori explained that this happens because of the way brains like to group people together.

“In predominantly white spaces, when you get to a bigger group, and you have to have a group in different ways,” Kanemori said. “So you might say white kids who have brown hair, white kids who have blonde hair, but oftentimes for students of color… we say black people or Asian people…because there are less of those in our lives.”

However, Kanemori explained that this does not excuse this mistake.

“I’ve been saying that it’s kind of natural that this happens, but that does not mean that it is okay,” Kanemori said. “It’s not just the one time you [did it], but it might have happened to that student three other times today in other classes.”

Senior Hebaq Farah has also dealt with this issue many times, often getting mistaken for other hijabi students in her grade.

“You tend to question whether you’re a memorable person,” Farah said. “Or if you’ve been doing anything wrong to lead the people to mix you guys up.”

Despite there being a much larger population of hijabi students at her old school, according to Farah, it was much less common for them to be confused with one another.

“When you come to a school where you’re like, one of three or four [hijabi students]…you would expect that the mixing up occurs less frequently,” Farah said. “But it’s a slap in the face when you realize that ‘oh, at my old school they could differentiate between us, but this school really struggles with a couple of one ethnicity.’”

As a result of being mixed up with other Mexican girls at school, senior Daniella Meza began to feel as though her identity is reduced to her appearance.

“It felt like there was a singular defining factor of who I was,” Meza said. “That’s what made me think that sometimes when people see me, they just see one specific thing about me, and then they go based off of that.”

A student of color, who didn’t want to be identified because of their fear of social repercussions, expressed the impacts of repeatedly being mistaken for others.

“It feels reductive…and like you’re not your own person,” they said. “You’ve worked so hard for something to like, distinguish yourself to, once again, be like lumped in…It feels like it’s insulting to how hard I’ve worked.”

Mira Hinkel is a staff member of the Puma Press, and this is her second year on staff. She enjoys writing news stories and covering student life. Her favorite...

Ilham Mohamed is the graphics editor of the Puma Press and has been on staff for two years. Her favorite types of stories to write are usually experientials,...