Isabelle Rio

French Teacher, Languages Department Head

Biography:

Haute Bretagne University, License, English;

Bourgogne University: License and Master in Russian

- Previously taught French at the Abington Friends School and Milton Academy and English as a second language in France and Spain, and had her own dance school

- Enjoys ballet, yoga, serving as a community volunteer, and practicing mindfulness

Background: Mme. Rio taught my French class for a semester. She helped me understand French grammar and also offered me insight into French culture and art. I could tell she had a passion for language, teaching, and learning, and I was excited to hear more about her childhood in France and her experiences in the United States.

Just from my time with you in French class, it seems like you have pursued many different interests and lived in many different places. Could you tell me about where your life has taken you?

My childhood was a very interesting time. I grew up in France during the Cold War. My father was a self-made man. We come from very humble origins. Education was a key value in my family. I’m the first to graduate in my family at the university level. I excuse my parents, of course, because they were children of the war. When bombs are falling, you don’t always have the time or the opportunity to go to school.

My father always said the languages of the future were English and Russian. So, I was a good little girl and obeyed, and I studied Russian and English as a double-major. I’m embarrassed now, because I don’t speak Russian—at the time it was more French literature or comparative literature with Russian.

After I finished my masters, I wanted to pursue Russian, and I thought it was time I went to the country to speak it. Unfortunately, at the time, you had to belong to the Communist Party to go to Russia and get a job as, say, a TA. I remember saying to my classmate: “no way am I going to mix politics and languages.” I do not mean to be entitled, but I have a right to learn the language. I don’t need to be part of the Communist structure. I was at a crossroad, and I said, “well, if they don’t take me, I go the other direction.” So, I applied, and got accepted by three Universities in the United States, among them IU Bloomington. I came to the United States, and I fell in love with the United States. I was fascinated by the American culture.

Interestingly, when I took my first plane flight to the United States, the first thing they asked me was, “have you ever belonged to the Communist Party?” to which I was like, “No!” I was so relieved to be able to answer that question with “no.”

What was your childhood like? How did growing up during the Cold War impact you?

France is peculiar because people think we’re a communist country but we’re not; we’re a socialist country. We have a Communist Party—In our spectrum we have many, many parties from extreme left to extreme right. You have the right to express your opinions, and people will vote for you or not. I believe that’s a true democracy.

I can only speak for my family. My father was a self-made man and worked very long hours. My parent’s roles were very defined. My father was the bread winner, and my mother was the homemaker. My dad wanted her to be independent, so he would give her a budget and open an account for her, because at the time you needed your husband’s signature to open a bank account. Those times are not so far from us.

It was a time of big changes. You had the European Union. Europe was being founded. I remember going to Spain early on in 1991, then returning to live there in 2001, and the infrastructure had totally changed. Roads and telecommunications were upgraded. In the past, you would have to go to a kind of store, a “Locutorios” to make a call, and it was rather complicated. 20 years later, it was like life is today. I’m sure all countries in the European community did the same, whether it was Italy, France, Germany, England, etc.

You’ve talked a lot about like growing up with this value of hard work. How does that experience shape you now?

I discussed this yesterday with my son. He said, “Mom, you don’t know how to relax.” Which is true. I never learned. Is it because I’m a perfectionist, or is it because I was educated that way? Is it because I was the eldest in my family? I don’t know.

Maybe this is why I am so comfortable in American society, because it’s all work and no play. You don’t take a nap a day, and you don’t go on big, long vacations, otherwise you feel guilty. You don’t take sick days.

I think this is wrong. Just because you work more does not mean you work more efficiently. In Europe, where there are different work cultures, people value their time outside of the workplace and still have good work ethics. I’ve worked with people in Spain, and they had great work ethics. The same with French people. But here in the States, you must be accessible 24 hours a day. That’s not right—people have families and lives. We need to find a more balanced way of living and working in the United States. But it’s shaped me, and I don’t know how to fix it. That work ethic. My goodness—too much.

I think this is maybe why I like mindfulness so much, because I’m teaching myself to be in the moment. I feel like I’m on this train, moving forward moving forward. And I need to enjoy the process.

You mentioned earlier being interested in the culture of the US. Why? What interests you?

I am very fond of discovering new languages, new cultures. I like to listen to people’s stories and see how they think and why. I came to the US because my country felt too small; I wanted to expand my horizon. The United States was a different experience, a parallel experience.

The problem to this is that I don’t belong to the United States. When you’re learning a language and learning a culture, you never totally 100% belong to that country. People sometimes tell me, “oh, you’re so cute, you have a French accent”—which I’ve been trying to lose, by the way—and I’m like, “No, I’m not cute! And, I wasn’t born at the foot of the Eiffel Tower, you know.” Come on, these are stereotypes. The beret, the baguette, the smoking a cigarette—I don’t smoke, I’m pretty much a vegetarian, and I don’t eat snails or frogs.

But when I go to France, they treat me like, “oh, you’re the American. You’re the one who left.” I don’t connect like I used to. I have family there, I file taxes over there, but I don’t belong to either world anymore. I’m in a no man’s land, or a Twilight Zone, in between two worlds.

Is there anything people at Uprep can do to make you feel more at home?

Well, now people spell my name, Isabelle, correctly!

French people are usually stereotyped as posh, pretentious, and arrogant. And I think a lot of the time, people see me that way. I’ve tried to show my kind side. But kindness doesn’t necessarily mean leadership. I’m not sure whether it’s the French part of me, but sometimes I feel like because I’m a woman, and I speak softly, people don’t respect my authority. I don’t count as much as someone big with a big voice who has grown up in the same culture as everyone else.

It depends on the day. Some days I feel good. I’m in sync with my community, everything is fine, and other times I feel invisible. So, take it with—how do you say—a grain of salt.

Now, that said, UPrep is a warm and welcoming community. Faculty and staff are always very supportive, and students are of course amazing! I always come to school with a smile.

Thank you for sharing. I don’t think I ever would have guessed you had those experiences.

Yes, you could ask some of my World Languages colleagues about it. Because we are white, we have privilege. And we blend in. It can look like there are no problems when in fact, there are.

It’s like being single. I’m a single parent. I think there’s a lot of discrimination, because society is built on marriage. People of my generation would say, “my wife” or “my husband” and now it’s become “my partner,” but still there are two of them. They’ve met their mates. It’s very anchored in society. When I show up to a party and say I’m a single mom, it’s like, oh, I’m a threat to society. I’m going to take their mate.

You’ve already touched on this, but I would like to know a bit more: over the past couple years, I’ve really realized that I’ve been raised with a specific mindset and worldview. And other people have drastically different ideas about right and wrong than I do. What types of values were you raised with, and how has your perspective changed as you’ve gotten older?

When I was younger, when I was your age, I was very idealistic. I believed in hard work, education, respect, tolerance, and equality.

After the second world war, my dad decided to have a couple of au pairs. And he wanted them not to be English, not to be Spanish, not to be Italian—he wanted them to be German. An au pair becomes like part of the family, and my dad wanted us to be exposed to peace. He wanted us to understand that yes, there had been a war, but now the war was over, and now we needed to reach out. Now we needed to embrace the other culture in peace.

I didn’t learn German because I was overwhelmed with my English and Russian and Spanish, but if I had continued, maybe I would have taken up German as well.

My ideal world would be a world of respect. I have my views, you have your views, and let’s live together peacefully. To live together with different opinions, I think that makes the world much richer, and much more interesting.

Sometimes I feel like society has changed because there’s a lot of entitlement out there. People say whatever they want on social media. Social media is not—please excuse the expression—but it’s not your place to vomit. If it is social, you need to be cordial. You need to be respectful of the other person, of all human beings, whatever color of skin, religion, culture, and language. In other words, think twice before you write because there is a real person reading it!

I’ve made mistakes! I’m saying this now because, when I was your age, I was like: “Revolution! Equal rights!” I’ve realized with the years that it’s hard to do that. It’s hard to live together and embrace each other. Some people speak with one side of their mouth, then do something totally different. I can’t stand hypocrisy. That’s my pet peeve.

Could you speak a little bit about your education? I remember in class, you mentioned once you’re your name didn’t get called during your first day of school.

I grew up Catholic. I’m a believer, but not in a religious kind of way, more in a scientific kind of way. I think there is something bigger than us, and I believe in a big puzzle.

I love when we had that presentation from Cinnamon Kills First. That was beautiful. I was very touched. It brings me to tears that we’ve been so mean to the planet and to humanity. I mean, humans have been the best, but humans have also been the worst.

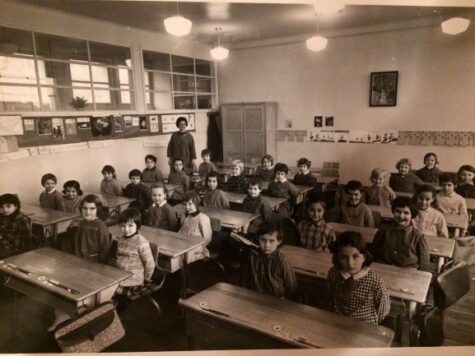

I went to Catholic school when I was a kid. But my dad believed in public, so I moved to a public school. It was a huge school—there were 2000 students. And there I was, a little munchkin. I was 10 in 6th grade. I had this big, big backpack on my shoulder. The first day of school, they forgot me—everyone left to go to class, and my name wasn’t called. I was standing all alone in the yard. The principal showed up and said, “what are you doing here? You’re supposed to be in class.”

“Well, nobody called my name!” I didn’t know what to do.

From that day on, they called me “la petite Rio.”

Once a bigger kid, I remember his name was Marc, tried to bully me—because again, I was small—and we started fighting. It was a really unbalanced fight. Finally, the teachers separated us and said to me, “don’t you dare do that again.” I told them he was being aggressive, and I think poor Marc got the worse punishment. I wanted the entire school to know that my size did not mean I couldn’t defend myself! Of course, now looking back, I could have used my words.

I was a terrible student at first because I was lost and didn’t know the system. I was smiling all the time and making jokes; I was a little bit of a clown. Then I became very serious and became a very strong student for the school. I even wrote for my newspaper at one point.

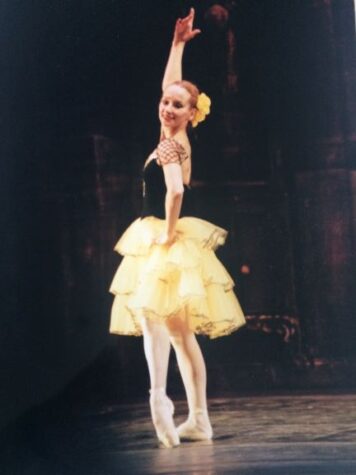

I just have to ask, can you talk about dancing? You’ve mentioned in French class that Ballet was a big part of your life.

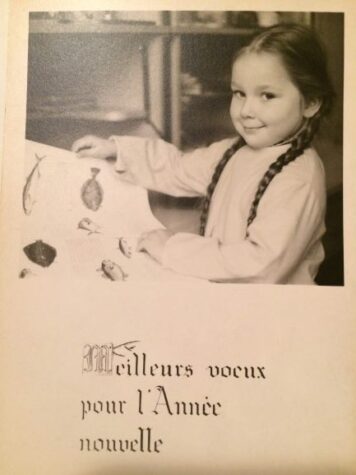

During my childhood I was allowed to take dance classes if I had good grades in school. I started dancing at five years old because my mom thought it was a very graceful thing for a girl to do.

I remember my first class very clearly, as if it was yesterday. They put me in a group with less experienced students. We were doing very basic things—stretching and butterfly arms. It wasn’t what I wanted to do. Then I remember going up the stairs and looking through the staircase into another studio. The dancers inside were doing pique turns on the diagonal, wearing those beautiful black leotards and their pointe shoes, and I said, “this is what I want.”

That was it. I was hooked for life, and whenever I could escape my French or Russian or English classes, you would see me in the dance studio. I also danced professionally. Not in a big company, by any means, but I did some solo work here and there when I came to the United States. I danced Russian classical ballet for all my life until I got injured. I even danced when I was pregnant.

What do you want students to get out of your French classes?

Love. Love for the other, for French culture. Even though English is spoken all over the world, make the effort to reach out to another person. Have tolerance, respect. No entitlement.

And continue with your French! Continue with your language, whether it’s French, Spanish, Mandarin, or anything else. Continue learning. I would love for past students to come back and say, “oh Madame, I spent the whole year in Belgique” or, “I went to Senegal, and I’m a different person because of it.”

Be a good diplomat in your life. I know kindness is not necessarily valued right now, but I think our society will change. Keep yourself a little secret garden or little place where you can go just for yourself, because sometimes being kind means you give and give, and no one gives back, so you need to regroup with yourself.

Your donation will support the student journalists of UPrep.