Student Article Prompts Reckoning in Sports Biases

Student-athletes of color tell their shared experiences

“I felt like I had to prove to the coaches that I had the same skills the white players did,” Shylynn Rodrigues wrote.

Rodrigues plays for University Prep’s girls frisbee and basketball teams. In November of 2020, she published an article on the frisbee-focused blog Ultiworld detailing her experience facing microaggressions in the UPrep ultimate frisbee program.

One of the main themes in Rodrigues’ arti cle was playing time. Rodrigues felt her coach played her and other players of color less than her white teammates in games. The coach would also treat players of color more harshly when they missed practice or did something wrong in practice, Rodrigues said. She also said she had a hard time fitting in with her predominantly white team.

cle was playing time. Rodrigues felt her coach played her and other players of color less than her white teammates in games. The coach would also treat players of color more harshly when they missed practice or did something wrong in practice, Rodrigues said. She also said she had a hard time fitting in with her predominantly white team.

“I think the biggest takeaway that I wanted people to get is that even though ultimate seems like such a big, welcoming community, there are still like microaggressions and discrimination seen within ultimate, especially with the people of color,” Rodrigues said.

While Rodrigues’ original article only applied to frisbee, she told The Puma Press that she saw similar issues of racial bias in the basketball program regarding playing time and coaching styles. And she’s not alone, because this inequity extends much further: athletes, coaches and UPrep administrators all see racial biases that hinder students of color from competing.

Biases on the field

According to Rodrigues, it was difficult to fit in with the white girls on her team.

“Players of color should not have to change themselves, ‘act’ more white or put on a mask when they step onto the ultimate field in order to fit in,” Rodrigues said in her article.

As a result, she spent more time with the other players of color on her team than the white players.

“I just feel like to an extent, sports teams can be cliquey,” Rodrigues said in an interview with The Puma Press. “So of course, the players of color would huddle together, and we would always talk together during practices and games. [We were] still interacting with the white players, but I feel like there is just not as much interaction between the two.”

Junior Jane Scroggs is Rodrigues’ teammate on the ultimate and basketball teams. Scroggs, who is white, doesn’t have to think about her race or face microaggressions that hinder her experience while on the field.

“[On the field], I think I have the privilege of knowing that I’m not not playing because the coach has an attitude against me, or is set against me because of the color of my skin,” Scroggs said.

When Scroggs read Rodrigues’ article, she was forced to reconsider the playing time she got in her freshman season of UPrep ultimate frisbee. Her sophomore ultimate season was canceled due to COVID-19 before games began, and her junior season began on March 29.

“I am one of the white players that benefited from the biases that UPrep athletics have. Like, I came on to varsity as a freshman and I had a lot of playing time. And I got a lot of positive reinforcement, and that made the sport really enjoyable for me,” Scroggs said. “I think like looking back, I didn’t deserve as much playing time as I got.”

Administration Efforts

Athletic Director Rebecca Moe heard about Shylynn’s experience for the first time by reading her article.

“I just wish I had known, [or] had some inkling sooner, that that was her experience,” Moe said. “Because moving forward, I don’t want another young woman to have an experience like that.”

According to Moe, Diversity, Equity and Inclusion work in coaching can be difficult, because UPrep hires coaches from two pools: current faculty and outside the UPrep community. Faculty DEI work in the classroom often doesn’t always translate to sports.

“We do a lot of coach training, but sometimes it’s more on the X’s and O’s, like first aid, CPR, concussion, sudden cardiac arrest [and] rules,” Moe said. “But I think we need to be making a more concerted effort at DEI work with our coaching staff.”

This year, Director of Diversity and Community E-Chieh Lin was in charge of the DEI section of UPrep’s coaches training. Mainly, Lin said her presentation focused on establishing herself as a resource for coaches in difficult situations such as race.

Her presentation did not include, though, an implicit bias training that she gives to her office every year. Bias workshops are an example of DEI initiatives within the athletics department that are developing according to Lin.

A Coach’s Reaction

“[Rodrigues’ article] reminded me that even though we’re all doing the work as faculty and staff, we need to do the work as coaches and sometimes that looks different,” Moe said.

Upper school science teacher and White Aspiring Allies club adviser Moses Rifkin coaches Rodrigues’ varsity ultimate team. While Rodrigues didn’t directly name Rifkin in her article, most of her criticism was directed at him, she confirmed in an interview with The Puma Press.

Rifkin has incorporated social justice issues, specifically surrounding race, in his physics classes. He has also worked closely with the Underrepresentation Curriculum Project to develop a STEM curriculum that focuses on identity. He hopes to bring similar DEI conversations to the field.

“I think…there’s an emotional intensity to sports that there isn’t for academics and that makes me think [for DEI conversations, the field] might even be a better place,” Rifkin said.

Rodrigues approached Rifkin months before she published her article, in the winter of 2020 to share her article and her experience in the ultimate program.

“I felt, at the same time that it was uncomfortable for me, that it was a real gift that she was giving me. And one that I felt really appreciative of even though it stung,” Rifkin said.

When the article was published months later, in November 2020, Rifkin had a similar reaction to when he first read the article.

“I’ve had these like, successive waves of intense experiences of gratitude and hurt and commitment to do better,” Rifkin said.

A Shared Experience

The racial divide reflected in Rodrigues’ article rang true for junior Paris Buren. Buren has been a member of the varsity basketball team since her freshman year. As one of the few people of color on the team, she felt a similar isolation to Rodrigues.

Buren also noticed a difference in critique from her coaches on the basketball team.

“My coaches tended to be a little harsher on some of us,” Buren said. “I don’t know for certain if that’s depending on race, but they wouldn’t really scold much of the other players that were white”

Rodrigues saw the same thing in the ultimate program.

“I definitely noticed that he would give us more critical [feedback] and critique us more on how we played while he kind of praised the white players,” Rodrigues said. “I definitely felt a lot more pressure from Moses, and I felt like that pressure wasn’t applied to like the other players on the team.”

Creating dialogue

According to student athletes, conversations about race are as important on sports teams as they are in class, in affinity spaces, or on Social Justice Day.

On her ultimate team, Scroggs said they had plenty of conversations about gender.

“I think we have had really meaningful conversations about gender on our team. And carrying that into, like, conversations about race would do a lot for our team and create [aspace] we can grow from,” Scroggs said.

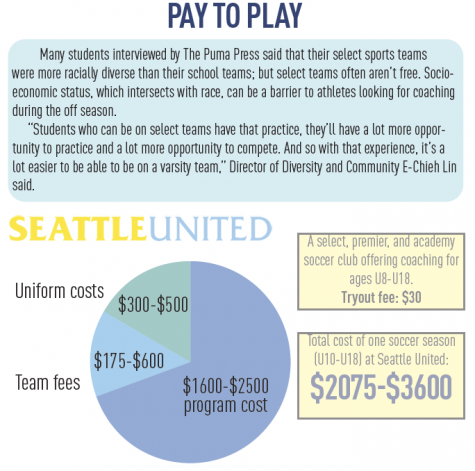

Buren believes that fostering conversations about race and other social justice topics on sports teams will help all players better understand systemic injustices in athletics. She thinks it is especially important for allies to stand with their teammates in these conversations.

“I feel like whenever we people of color talk about [race] the coaches tend to, like, sort of brush us off and stuff,” Buren said. “So maybe if they hear from the white players as well, that would help.”