The Trade-Off

Transitioning to private school, some teachers leave a higher salary for a smaller, independent setting

Photo: Mauricio Garcia

History department head Karen Sherwood took a salary hit when she took a job at University Prep seven years ago, coming from a public school. That public school, Mercer Island High School, also awarded her a large annual bonus for having a national board teaching certification, a bonus she doesn’t get at UPrep.

While public schools pay more than private schools like UPrep, teachers often find meaning in teaching at private schools because of benefits like smaller class sizes and higher salary mobility.

Public school teachers in Washington State have seen large increases in salaries over the past few years, while Sherwood has been at UPrep. These raises have been the result of negotiations between teacher unions and school districts. Those increases have reset the job market and forced other schools to make pay raises.

The Washington State Legislature earmarked $2 billion for increases in teacher salaries for the 2018/2019 school year, according to the Washington Education Association (WEA). This corresponded with a 10.5% increase in Seattle Public Schools (SPS) teacher salaries, according to the Collective Bargaining Agreement for SPS.

This agreement is the result of a negotiation between the Seattle Education Association (SEA) and Seattle Public Schools. The SEA organization is a part of the Washington Education Association, which negotiates salaries at public schools across the state.

The WEA is the union group to which most public school teachers in the state belong. Unions work to negotiate better salaries for public school teachers within each public school district; this process looks very different at UPrep.

Spanish teacher Alma Andrade is currently in the second year of her three-year term as the teacher representative on the Board of Trustees. Andrade has been a Spanish teacher at UPrep for 20 years. This is her first and likely last term on the board, which she said is typical.

Board leadership often asks Andrade to speak on behalf of all teachers at the school. She’s a member of the Human Resource Committee for the Board, which is consulted in determining teacher compensation; however, Andrade says, the Finance Committee is responsible for a final recommendation to the rest of the board regarding salaries.

“We’ve still recruited public school teachers to UPrep, even if we pay less,” Lansverk said.

The Finance Committee’s recommendation for the whole budget, is taken in front of the complete board of trustees, including Andrade, for a final vote.

Trustee, Chair of the Finance Committee, and Treasurer Mark Britton says the committee bases their salary decisions mainly off of other schools.

“UPrep considers both private and public faculty salary market data when determining faculty salary increases,” Britton said. “However, we weight private school data most heavily in our review.”

Assistant Head of School for Finance and Operations Susan Lansverk mentioned that despite UPrep’s lower pay, the school stays competitive for attracting teachers.

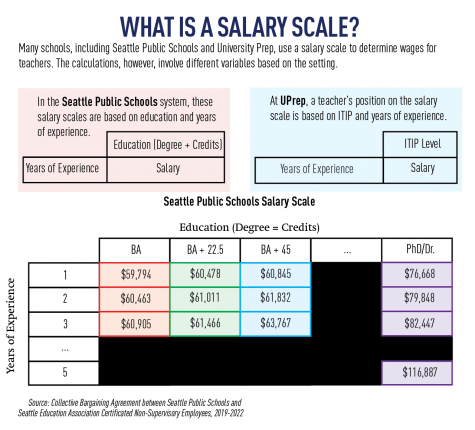

Both public schools and UPrep determine a new teacher’s starting salary based on their experience and education level.

Public schools and UPrep alike use a “salary scale,” which is a table that determines a teacher’s base salary.

Salary scales for UPrep are not publicly available. The Puma Press attempted to collect figures on teacher’s salaries at UPrep through an anonymous poll but was unable to obtain enough data to be statistically significant.

Public school salary scales, though, are public record. According to the Collective Bargaining Agreement between Seattle Public Schools and Seattle Education Association, a teacher with a doctorate degree in their first year of teaching will be paid up to 28% more than their colleagues with a bachelor’s degree in the same year.

Each year, Assistant Head of School for Academics and Strategic Initiatives Kassissieh said, a teacher will progress down the scale one row because they have another year of experience. However, at many schools not including UPrep, it’s more difficult to progress from column to column, which is determined by education.

Richard Kassissieh stressed how difficult it is to get a large wage increase at those schools.

“If you’re a teacher at another school and you want to make a bigger jump in your salary, you have to go [back] to college … and get a more advanced degree or take graduate level courses,” Kassissieh said. “That costs money.”

At UPrep, however, teachers follow an Individualized Teacher Improvement Plan (ITIP), which is designed to improve teachers’ classroom skills without requiring them to pay for more education.

Unsurprisingly, Kassissieh said, the ITIP program is a draw for potential teachers.

“The idea that we are supporting teachers’ continued growth absolutely is a draw,” Kassissieh said.

History teacher Dave Marshall, who is in his fifth year at UPrep, said ITIP differentiated UPrep from other schools during his job search.

“Pretty quickly, [UPrep] became my number one choice and ITIP was a big reason,” Marshall said. “It provides not just accountability but a space for reflection and research.”

UPrep provides funds for its teachers to attend conferences during their ITIP cycle.

“We reimburse expenses for professional development, and we do so at a rate that’s high compared to other schools,” Kassissieh said.

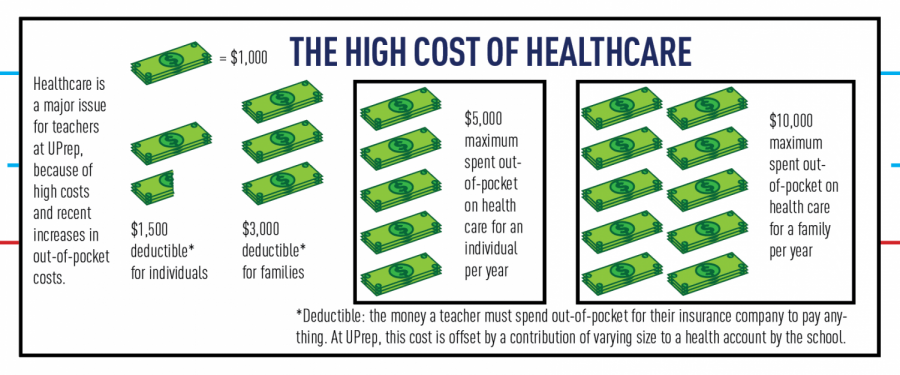

These funds are one form of compensation afforded for teachers at UPrep that isn’t necessarily counted as salary. Computer science teacher Tracey Sconyers said people often overlook benefits as a whole.

“There’s a lot of focus just on salaries, but benefits are huge,” Sconyers said.

Sconyers said benefits and health care in general are poor in America.

Caprice Pine, the Human Resources Manager for teachers at UPrep, said health care premiums, the out-of-pocket costs for teachers, were raised by 18% for 2020. However, Pine said, the increase didn’t affect everybody.

“The increase only applied to employees who are covering dependents or who are working less than 40 hours per week,” Pine said. “UPrep covers full-time employees at 100% for their own medical, dental and vision coverage.”

Pine works closely with Alliant Benefit Services, the company in charge of negotiating health care rates for teachers at UPrep.

“The increase for all employees came in much higher, but the broker was able to get it reduced to 18%,” Pine said.

Pine said claims from the past year informed the higher rate for this year.

For Sherwood, healthcare isn’t a downside at UPrep.

“I’m actually really happy with the health care plan I’m on here at UPrep,” Sherwood said. “But it does cost me more than it cost me in public school.”

Even though Sherwood is compensated less at UPrep than at her old school, the decision to teach at a private school comes down to class sizes and her relationships with students.

“I really wanted to get to know my students a lot better,” Sherwood said.

UPrep has worked in the past few years to make sure teachers have a maximum of 72 students total at a time, with a maximum of four sections per semester and 18 students per class, Kassissieh said. At Mercer Island High School, Sherwood taught more than 150 students at a time, with five sections per semester and upwards of 30 students in each class.

“It’s much more satisfying to have smaller classes [at UPrep], being able to spend more time on your students,” Sherwood said.

The Power of Student Voice: Q&A with Alum Sasha Shenk

Sasha Shenk was a senior at UPrep when she undertook a project based on increasing parental leave for teachers and faculty. She was ultimately successful, and today teachers and faculty enjoy a more progressive parental leave policy.

Can you describe the work you did for the parental leave project? Why did you do that project?

It was actually born from me finding out that UPrep didn’t offer any compensation to teachers when they went on maternity/paternity leave. The previous policy granted teachers three months of unpaid leave, and they could use all of their accrued paid sick leave for compensation but otherwise did not have any financial support while they were gone…The more that I dug into this project, the more I discovered about what I felt was a very unfair policy. Most notably, for a faculty member to be able to take 3 full paid months off, they would have to work six straight years without a single missed day to accrue enough sick leave…all of this research culminated into an open presentation that I had one day after school in Walden.

Who did you do the project for/with? Who do you think it most affected?

I did this project completely on my own because it’s something I am genuinely passionate about, and UPrep definitely fostered a desire in me to question things that I felt were wrong. This entire experience taught me a lot about how to execute activism, and to try and better your community when you see something that you personally feel is unfair. Things aren’t always so simple, too. As I got older and went through college I definitely recognized that UPrep was doing the best they could for their staff, and their open-mindedness to change when I approached them was really inspiring.

Your donation will support the student journalists of UPrep.