You Get What You Pay For

How wealth gives college applicants the upper hand throughout the admissions process

May 22, 2019

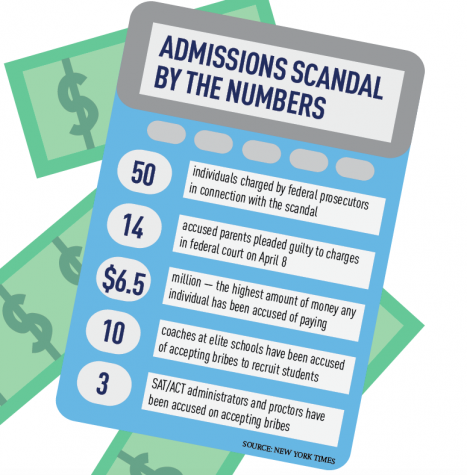

As University Prep seniors received their college decisions, national headlines detailed a college admissions scandal involving parents accused of collectively paying millions of dollars to ensure their children spots at prestigious institutions. While parents involved in this scheme now face possible prison time, there are many ways that money can legally play a role in the application process, too.

On top of enumerated lists of extracurriculars and meticulously crafted essays, a family’s wealth — or lack thereof — can influence a student’s chance of admission. Long before a student approaches senior year, financial status may indirectly affect a student’s chances of admission by determining access to high-quality secondary education from schools like UPrep. Students whose families can afford to send them to a private school often have greater access to resources than students attending a public school.

While a private education helps students prepare for college academically, resources at these schools can also give students a leg up during the application process. Many private institutions offer extensive, personalized support for applicants that may not be available to students at public schools. At UPrep, students have access to two, full-time college counselors who meet regularly with every student.

“I think we have amazing college counselors, and they really get to focus on you as a student,” senior Ani Pigot said. “At other schools, I’ve heard my friends say they’ve only seen their counselor once.”

At Roosevelt High School, five college counselors are available for 1,877 students, as of the 2017-18 school year.

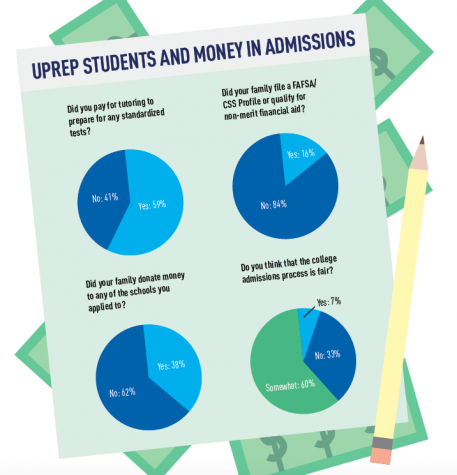

In addition to admissions help within schools, students who can afford it can also benefit from tutoring for support with schoolwork or in preparation for standardized tests such as the SAT and ACT.

“A lot of students will pay extra for standardized test preparation and tutoring, and that can be incredibly expensive,” Associate Director of College Counseling Britten Nelson said. “We know that standardized tests are, in many ways, biased towards people with more money.”

Senior Maddie Laferniere feels that she was able to benefit from tutoring to help prepare for standardized tests.

“I got to go to tutoring twice a week,” Lafreniere said. “If you can’t afford it … you’ll have a harder time figuring out the test. I don’t think it’s fair.”

While the college application process is affected by indirect costs such as private school tuition and tutoring, it also includes many direct costs, like fees for taking standardized tests, sending scores to colleges and submitting applications.

For these costs, however, testing agencies and colleges usually offer need-based waivers. Senior Hanan Sherka explained that while fee waivers were helpful for her family, they didn’t cover everything.

“There were a lot of waivers [available] if you couldn’t afford certain things like getting your ACT scores sent to schools,” senior Hanan Sherka said. “My family income is pretty low, so a lot of those costs got waived, but tutoring for testing and stuff like that, I didn’t get [anything].”

Senior Kalil Alobaidi also sees how affording college can be challenging, even for students who don’t qualify for financial aid.

“It’s especially unfair for the students who are in this weird gray area where they don’t qualify for financial aid, yet their parents are struggling to afford different schools,” Alobaidi said.

In the admissions process itself, a student’s financial status — including details like whether a student can pay full tuition — can directly influence their chances of being admitted to a college.

“I’ve seen it play out where I know that a student had the right grades and the right test scores, but they were also not going to be inexpensive to enroll,” Nelson said. “The need-blind schools would take that student, whereas the need-aware schools would not.”

Senior Flannery Daley-Watson thinks that her family’s financial means may have helped her gain admission to the school she plans to attend, Pitzer College.

“I think the fact that I could pay for my whole tuition played a large role in my acceptance,” Daley-Watson said. “At Pitzer, they work really hard to provide as much financial aid to students [who] need it, but that means other students need to pay full tuition so they can provide [that].”

Although The Puma Press was unable to verify that Daley-Watson’s finances played a role in her admission, Assistant Director of Admissions at Pitzer College Dwayne Okpaise confirmed that Pitzer operates with a need-aware admissions policy, considering ability to pay tuition as “one of the many factors that we look at.”

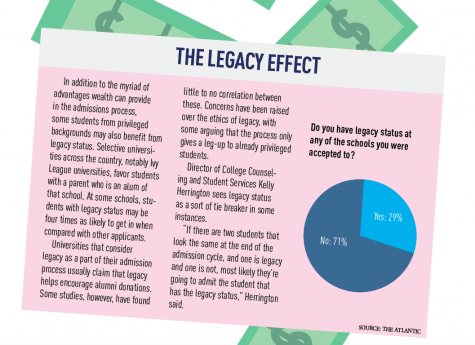

In addition to an applicant’s ability to pay full tuition, some colleges take into account the family’s capacity to make significant donations, according to Nelson.

“The institutional research and development offices do partner with the admission offices to figure out who is likely to donate money, and that can open up some doors for students,” Nelson said.

Other schools seek to separate a family’s ability to donate from their admissions process. Seattle University Director of Admissions Katie O’Brien explained that Seattle University does not consider a family’s ability to contribute when making admissions decisions.

“I have had family members hint that they’re planning to make donations if their student is admitted, to which we direct them to the Advancement Office,” O’Brien said. “We say, ‘Great, that has nothing to do with admissions. If you would like to support the school financially, you can go through this channel.’”

Similarly the University of Washington does not take an applicant’s ability to pay full tuition or make donations when making admissions decisions, instead using socioeconomic status to put students’ applications into perspective. As University of Washington Director of Admissions Paul Seegert explained, a student’s financial background is only considered to help admissions gain a fuller understanding of that student’s opportunities.

“I think we have a good balance of considering academic preparation and performance, but balancing that with the realities for students who come from backgrounds that aren’t as privileged,” Seegert said. “Statistically, if someone’s parents didn’t earn a college degree or even go to college at all, students who come from low-income backgrounds, it’s harder to achieve in high school, and so we take that into consideration.”

Though many schools, like University of Washington and Seattle University, do not consider a student’s financial needs when making admissions decisions, at UPrep, where 85% of students are able to pay more than $30,000 in tuition, most students don’t have to worry about their financial status hurting their chances of admission. Director of College Counseling Kelly Herrington feels that most students do not realize this privilege.

“All [students] know is UPrep, so they’re not quite fully aware,” Herrington said. “This is not their fault, nobody’s to blame for this, but if [UPrep] is all you know, you feel like this is the reality that’s out there for the greater world.”

Having just completed the application process, Pigott reflected on the inequities she sees at play in college admissions.

“I think there’s a long way we have to go until it’s fair,” Pigott said. “There are a lot more measures we have to put in place to make sure people can get over barriers and have a fair chance.”