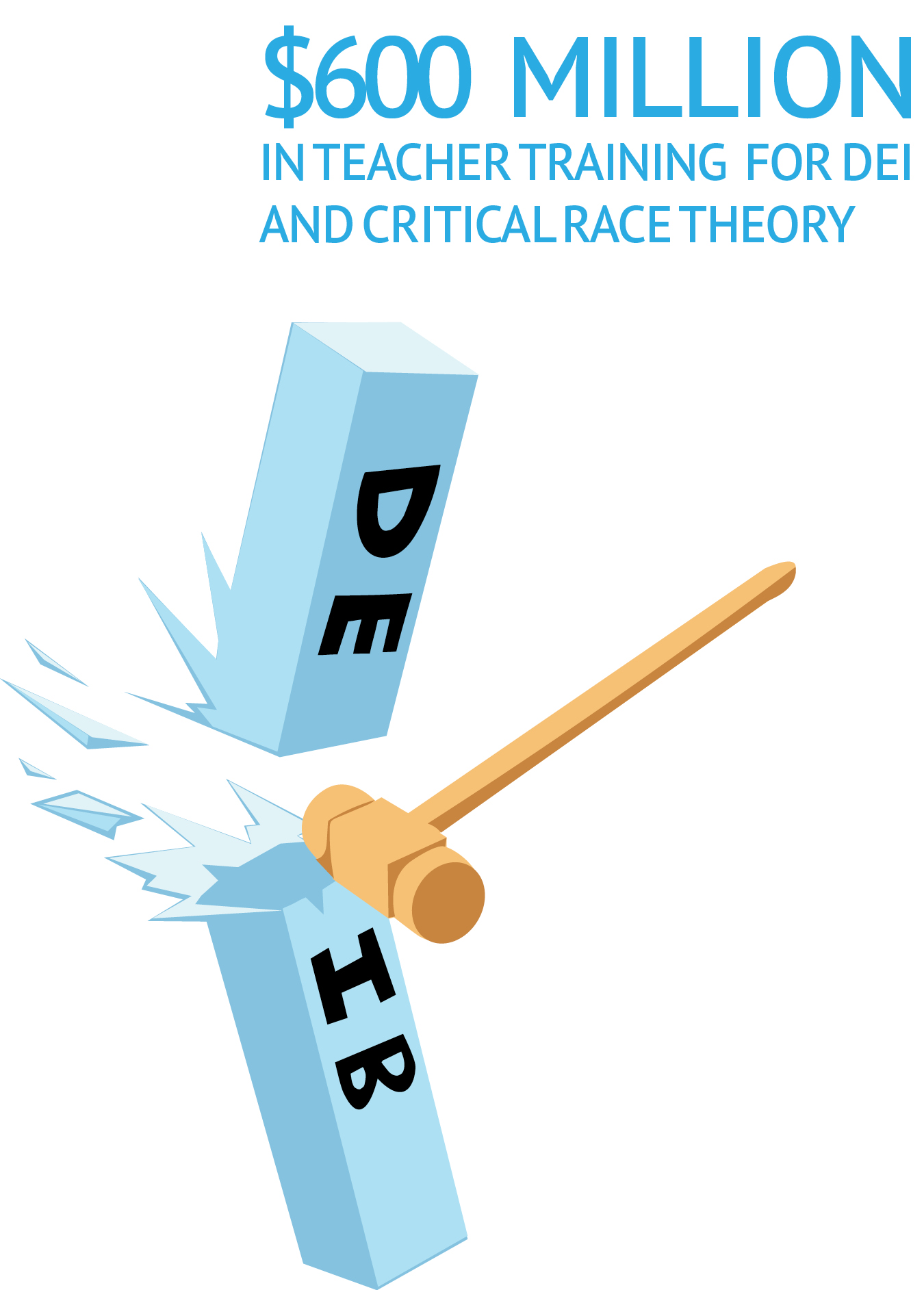

Across the nation, schools are eliminating inclusive practices by the name of Diversity, Equity and Inclusion programs. The Department of Education announced that it had cut $600 million in teacher training funds that were promoting what it called “divisive ideologies,” including DEI and critical race theory, according to a report by Reuters. For many, these programs are seen as an unnecessary luxury in the face of budget cuts and political push back. But UPrep is defying the trend and continuing to stand by these programs and initiatives.

Director of Diversity, Equity, Inclusion, and Belonging, Taylor Kanemori, has directly worked in the DEIB field for the last seven years. Though worries about the future of DEI are rampant, Kanemori affirms its stability.

“This is nothing new. It looks a little new in some ways, or it feels a little bigger in some ways because of maybe specific policies, but I mean when we talk about specific racism or sexism or homophobia or whatever, these have existed forever,” Kanemori said. “The people who are combating that work and trying to do good work in those fields have had many things thought about them. For a lot of us in DEI work, we’re like, ‘Okay, this is the next thing’, and here we are trying to continue to do what we can.”

Senior Rory Cox-Hultquist, leader of Queer Student Union, has hosted meeting for the group that talk of the political state of the country.

“The whole thing that the Trump administration is strategically trying to do is erase all mention of people who the Trump administration thinks are deviant to the norm, which is censorship because that’s information and history that we need to know,” Cox-Hultquist said. “Let’s be honest with ourselves when they say DEI. People of color, queer people, anyone who doesn’t fit the Trump administration’s mold.”

Despite concerns about DEIB initiatives fading, Kanemori insists they will continue.

“I think some of the conversations feel a little bigger and sometimes a lot heavier than maybe they have when things were a little bit more positive in our world,” Kanemori said. “But for most of the practitioners that I’ve been talking to, yes, there are some things we’re talking about that we weren’t before, but in the grand scheme of things, we’re still just trying to do the work that we have planned and set goals for.”

Despite Kanemori’s optimism, Cox-Hultquist believes that the denouncement of DEI extends beyond just attacking programs.

“The rollbacks on DEIB are kind of a direct attack on many people, including queer people. You see a bunch of the rollouts very directly affecting specifically trans people, just erasure of any mention of the trans community,” Cox-Hultquist said. “The legalizing of only two sex markers, really erasing that whole community of people on any official documents or official websites, the mentions of the word ‘transgender’ are being removed. This kind of erasure of not only history but identity and a whole population of people who don’t feel like they are real and seen in the U.S. anymore.”

Cox-Hultquist highlights the broad impact of DEI, emphasizing its role in advocating for all marginalized communities.

“DEI affects transgender people a lot, but it really affects everyone. It also affects gay people,” Cox-Hultquist said. “The biggest thing that DEI affects is a lack of information, which I think not only impacts queer communities and people of color, but everyone because information is the most powerful thing a person can have. I think we should all be worried about censorship.”

Cox-Hultquist feels as though QSU allows a space for queer students to feel most comfortable and talk about issues in the community with “like minded peers.”

“I think that no matter who it is, erasure of a community should be scary to everyone because that means that they are willing to do it based on something arbitrary about you. I think that people who think they are safe because they think it’s not them don’t understand the gravity of the situation,” Cox-Hultquist said. “It’s a slippery slope, essentially, once you stop respecting the sanctity of other people’s identities, I think that anything is fair game for someone to strip away from you. And it’s about rights. It’s about your right to yourself and your self-expression.”

Senior Anthony Chavez-Cruz, leader of Latine Student Union (LSU), appreciates having affinity groups because “people can stay connected with their backgrounds.” Affinity groups allow space for minorities to feel a sense of belonging.

“It’s nice having my community inside of a community where there aren’t really a lot of us. It’s a place where we all can be together,” Chavez-Cruz said. “We can all communicate about the same issues or the same problems without having to worry about what others think.”

Though Chavez-Cruz has found community in the group, he initially did not see the value of affinity spaces.

“As a freshman, I didn’t want to go to LSU, and I thought it was stupid because I thought, ‘Oh, it’s just going to be boring, they’re gonna be talking about this stuff and that stuff,’” Chavez-Cruz said. “But then once I did start going, I really saw the purpose of it. And I was like, ‘Wait, this is important. Why am I missing out on this?’”

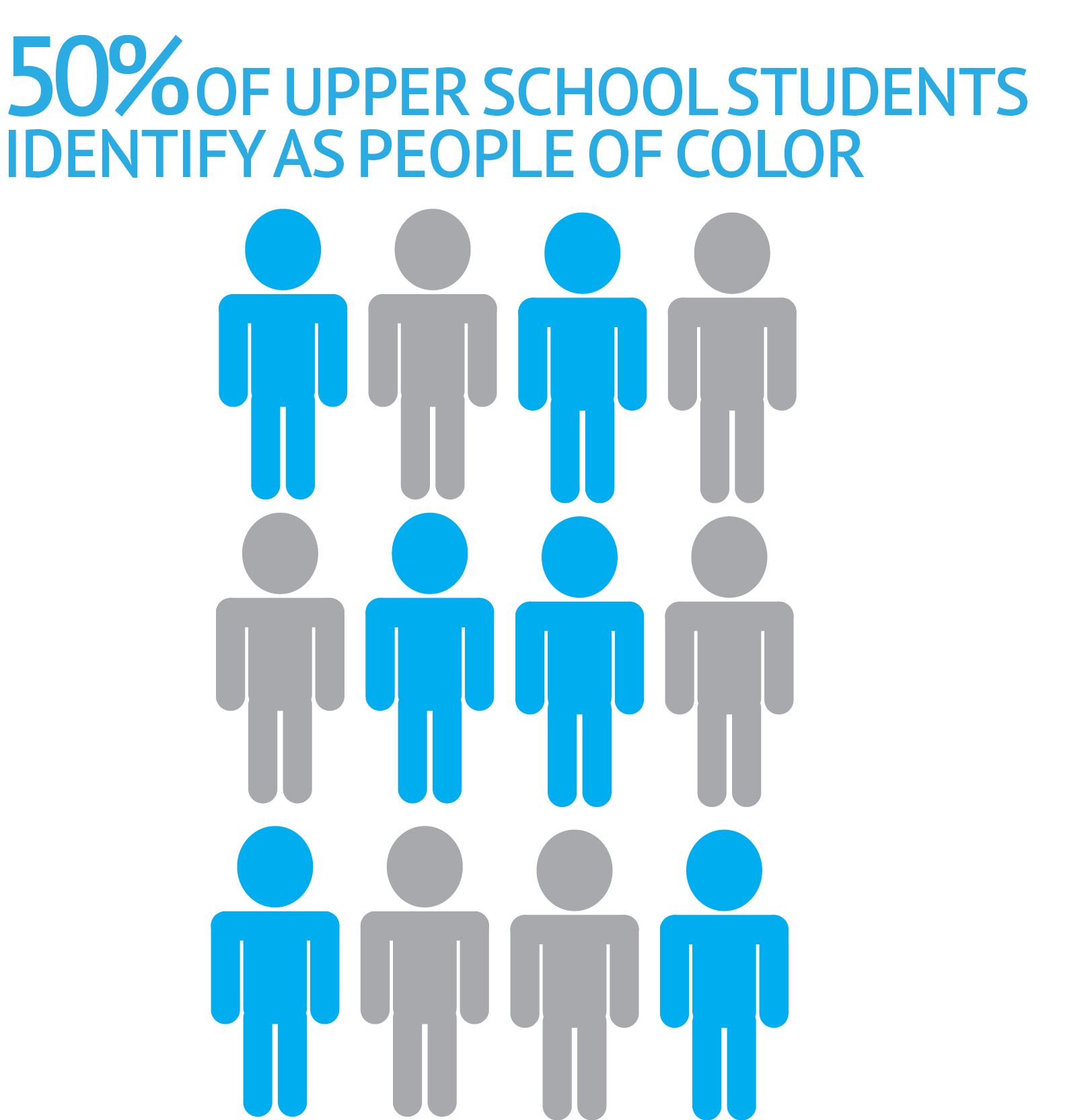

Though approximately 50% of UPrep’s population is POC as of this year, according to Kanemori, Chavez-Cruz feels as though the large white population overshadows other racial groups. Because of this, he is able to identify with other POC because of shared challenges.

“I can connect more with other people of color because we are a minority group, and that’s a new way to open up conversations and get to know each other better because I just think understanding others’ situations is important.”

Jeff Birdsall, an educator, trainer and facilitator, has done DEI work through these opportunities. He has done DEI work for 20 years, starting at a time when there was hesitancy in conversations around “power, privilege and equity.”

The state of Washington faces a multibillion budget shortfall. Birdsall does DEI work and projects for the state, but some projects have been canceled as federal anti-DEI laws are dismantling state initiatives. State DEI policies still apply no matter the federal-level pushback, but there has been some panic in the gray era. Additionally, many DEI workers have been losing their jobs due to the new policies, according to Birdsall.

“As a community we have to think about how to support not only people right now who are marginalized, we have to think about how to support all the people who are losing their jobs because they are connected to DEI,” Birdsall said. “How do we provide a space to not lose their wisdom and keep education happening?”

Although the acronym DEI only emerged over the last decade, according to Kanemori, and DEIB surfaced within more recent years, the work has been around for centuries.

“The idea of making sure that equality and equity are being instituted for all folks, people have been thinking about how to do that work for a long time,” Kanemori said. “DEI work is all based on feedback. Like the group is not getting what they need, or individuals with disabilities aren’t getting what they need, and they’re telling people, ‘Hey, we need these things’, and then it’s like, ‘Okay, how do we make sure that we are providing those things for people?’”

With DEIB work relying heavily on input for the advancement and progression of inclusion practices, progress takes place when DEIB practitioners, like Kanemori, listen before acting.

“We think so often about this work being proactive, and there’s a way in which we definitely want to be proactive. But there’s also the reality of this work being pretty reactive in a lot of ways, too,” Kanemori said. “There are going to be things that we don’t know exist or come to the surface until they come to the surface or are told about them explicitly. Our job is to learn what’s the best way to move forward to make sure that people are getting what they need, or that we’re making sure that spaces have many voices.”

In Birdsall’s 20 years of working with various organizations to instill DEI initiatives, he has seen efforts come to fruition.

“DEIB work has helped teams really come together and build relationships across differences because if you don’t talk about it, sometimes people are just living out their prejudices and unconscious biases, not because they’re mean people, but because we all have that stuff implanted in us,” Birdsall said. “I’ve seen that a lot over and over again. When you spend the time to do good work, and people become not afraid of DEI but realize the benefit of exploring together, that can be really helpful.”

The longevity of DEI initiatives has caused the work to take shape in many different forms, according to Kanemori.

“This work has looked somewhat different at certain times, but has always been, at times, misunderstood,” Kanemori said. “MLK, who we know, like many, look back, and what an amazing leader and a person who brought forward all these things, but you even look at the headlines that were written about him when he was doing his work and it was demonizing him.”

Birdsall emphasizes the importance of reframing the conversation in a way that is more positive and open.

“I think we have to get away from the idea of political correctness. Instead, I used to talk about being socially responsible. We should be doing things because they’re socially responsible, not because there’s a right answer that someone else told us or that you’re going to get in trouble if you say the wrong thing,” Birdsall said. “We also have to get off of the extremes that DEI is somehow bad, and it’s something we shouldn’t name or say.”

DEI can mean different things to different people. For ninth grader West Wang, it comes with a price, as he doesn’t believe it’s “good for our society.”

“I think it kind of means it’s like radical empathy and radical inclusivity. It’s like, we’re going to try and be as diverse as we can be, but often that comes at the expense of other people,” Wang said.

Though Wang does not hold diversity at the top of his values, he feels that the upkeep of initiatives is up to the establishment.

“I don’t really think that I need to be around people that are necessarily similar to me. I come from a multiracial background,” Wang said. “I’ve never really thought of race as a big part of my life.”

Birdsall values celebrating differences in identity and connecting based on them.

“I personally want to live in communities and a society that value and respect diversity and difference and treat each other in good ways, even if we’re different- and we have similarities too- but trying to understand all those things and appreciate each other,” Birdsall said.