Mental Health

It’s Sunday night. You have homework due in three of your classes tomorrow, two major assessments due later in the week, and a math test. It’s hard to keep up, because if you don’t do the homework and work on the bigger projects, your homework grade slips, but if you do the homework and don’t study for the assessments, your grade also slips. In the end, the anxiety is too much and you end up doing nothing. Shoot.

Of 45 students polled across all four grades, only 15.5% ranked their stress due to grades as a 5 or below; the remaining 84.5% ranked their stress as a 6 or above on a scale from 1-10, with 10 being the most stressed. Is this just regular high school pressure, or is there something that can be done?

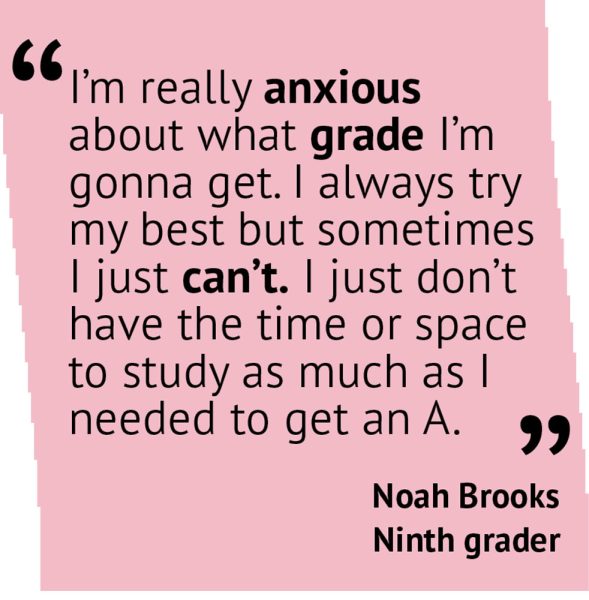

“I feel anxious, especially when it’s getting to the end of the semester. It’s a lot more stressful,” ninth grader Noah Brooks said. “It definitely also has to do with the amount of work I put into getting a grade, because if I work really hard, I’m really anxious about what grade I’m gonna get. I always try my best but sometimes I just can’t. I just don’t have the time or space to study as much as I needed to get an A.”

With the quarter ending on Mar. 19, the stress is already mounting. As a junior, Jin Hyun feels the pressure of grades very strongly, ranking his stress a 9 out of 10.

“Of course, this is more of an impression rather than the actual reality. But classes are picking up a lot,” Hyun said. “You become more concerned about your grades in the face of college. I think [the stress] is definitely rising compared to sophomore year.”

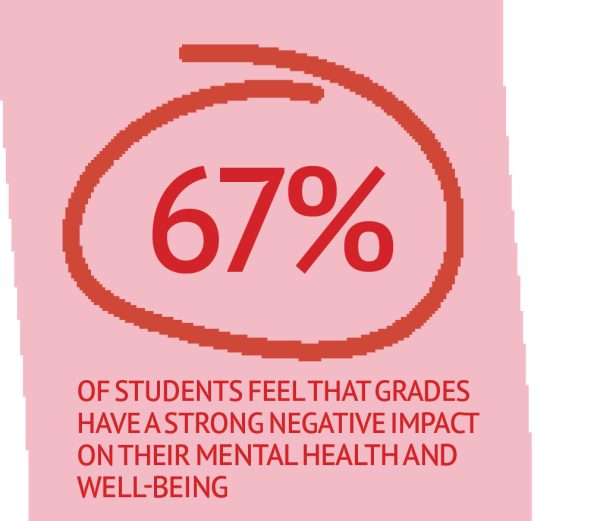

Anxiety plays a large role in decreasing a student’s mental health. In the same poll, 82.2% participants rated the negative impact of grades on their mental health a 5 or higher, with 10 being the most negative impact.

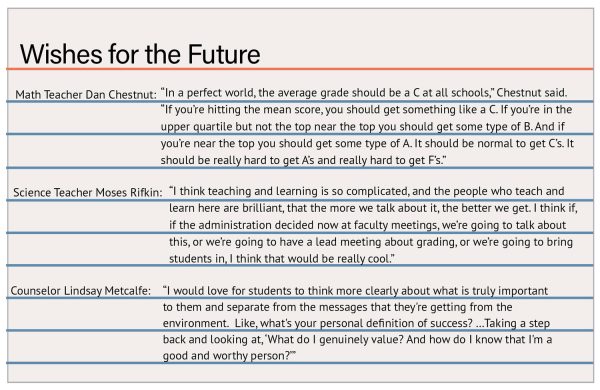

“There’s a lot of time and energy spent on that worry,” counselor Lindsay Metcalfe said. “I think that people leap ahead to thinking about the outcome, and it makes them less present and less engaged in actually doing the task, or taking in the information in class.”

Brooks and 16% of the polled students believe UPrep balances grade-based stress and inter-student competitiveness better than other institutions.

“I personally don’t feel like I’m competing with other people,” Brooks said. “I definitely feel like I’m comparing myself to what other people get, but I don’t feel like I’m competitive about it. I’m just trying to do my best…I shouldn’t be worried about the grade they get versus the grade I get.”

However, this does not mean UPrep’s lack of present competition creates none at all.

“I feel like a lot of kids have sort of either self-imposed pressures or parental pressures to perform well,” Hyun said. “And that creates a sort of a hushed up background culture of micro-competitiveness, [UPrep] doesn’t include class rank or anything like that, so it’s sort of behind the scenes where students keep that culture in the back of their mind.”

But even with a spectrum of student perspectives, grades are an important part of student life. The majority of students care about their grades, yet many differ as to why.

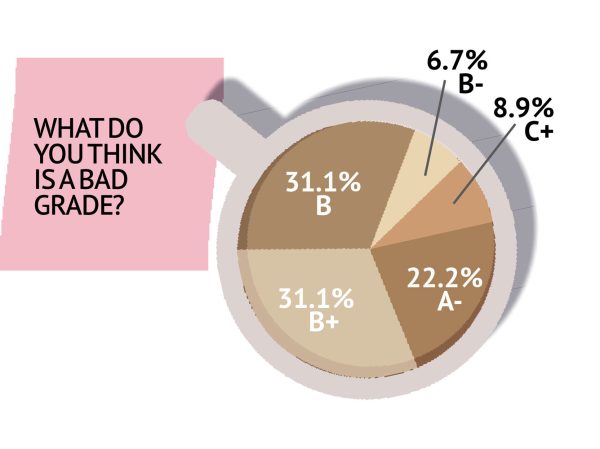

Of the upper schoolers polled, 23% believe an A- and below is a “bad grade,” 33% believe a B+ and below is a “bad grade,” with another 33% believing a B and below is “bad.” Only 11% schoolers believe a C+ and below is a “bad grade”– the lowest scoring option on the survey.

For senior Cate Fitzgerald, this bar is a B or below.

“The thing is, I’ve gotten A’s and A-’s so I know I’m capable of getting it, so it’s not so much a bad grade, it’s more of a, ‘I can do better,’” Fitzgerald said. “I know a lot of people don’t allow themselves to get below an A, so I think it depends. I feel like I’m in the middle, but I do strive for the best because I understand that if I put my best foot forward, it’s achievable.”

Hyun is one of the 10 students who ranked anything lower than an A- a “bad grade.” For him, the standard is just too ingrained to easily let go.

“I hold high standards. So I say, ‘anything under an A or an A- is a bad grade,’ even though realistically speaking, it isn’t.” Hyun said. “Some students are doing quantitative physics, they’re doing calculus, so you have to set a more realistic expectation. And I don’t think I’ve even reached that point. I think I’m still trying to convince myself that I can hold this perfect 4.0 or higher standard.”

But yet again, there are nuances that emphasize the complexity of grades and the grading system.

“Sometimes the only way to enforce learning is through grades,” Hyun said. “So I think the fact that they’re both connected together makes it very difficult. But I think, honestly, even if we could change the culture around grades at UPrep, I think it would be nicer to have more emphasis on the learning piece. It would take away a little bit more from the stress of grades.”

On the teacher’s side of things, a lot of the same discussions are happening. science teacher Moses Rifkin has been vocal about being open to conversations about grades and grading in order to create a better learning environment for his students. Six years ago, Rifkin completely overhauled his grading system, switching from a points-based system to a mastery-based system.

“I never really blamed students for wanting to talk about points because, like, grades really matter,” Rifkin said. “And I get that, but I was accidentally shooting myself in the foot by creating a world where points matter a lot, and if I shifted to, their learning matters a lot, then we’re now we care about the same thing…and now what students are asking is like, ‘Oh, I got a meets proficiency on this quiz. How can I learn more so I can do better?’ They’re not asking questions about points.”

Metcalfe wishes to see students let themselves learn more, rather than focus just on the grade, even though it may be difficult to disconnect.

“I see people measure their success by what letter is on the report card in the end, and not by, ‘Did I learn something new? Did I push myself to excel at something? Did I work through a challenge?’ Like that kind of stuff.” Metcalfe said. “I think that [grades] are not unrealistic, exactly, but it’s not a complete picture of what’s happening for that student.”

College

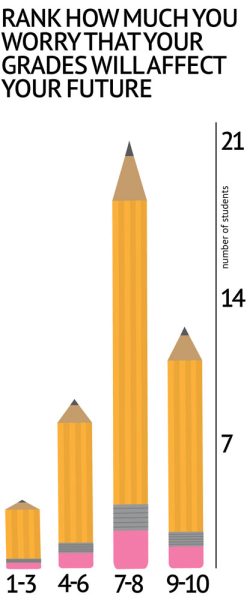

Hyun, Fitzgerald and every student polled indicated that they were in some way worried about how their grades would affect their future, and there is one looming threat that comes ever closer as the classes get tougher and the pressure gets stronger: college. Rifkin, who has taught at UPrep for 20 years, has noticed this mindset in his students.

“What I have seen is that the pressures of college have always been intense and are getting intenser, so the perception of ‘Uou need to have a 4.0’ feels more real than it used to,” Rifkin said. “It’s getting scarier out there. Admission rates are dropping and that pressure has always been at like eight, and now it’s like at a nine or a 10.”

Don’t just take it from teachers, college is top of mind when it comes to students, too.

“Grades are important, especially when I’m in high school and going into college,” Brooks said. “I feel like it’s important to get into a good college because it will have a large impact on what I do for the rest of my life.”

Overall, much of the stress ultimately comes down to individual expectations and student-driven goals rather than outside pressure.

“College and myself are the main [stressors],” Fitzgerald said. “There’s just an expectation that you’re going to get A’s and that that’s what’s supposed to happen. And, yes, that does happen, but I think that I put a ton of pressure on myself.”

This being said, the college process goes beyond grades. Cris Monroy has worked as a UPrep college counselor for the past three years and previously worked as an admissions officer, reading students’ applications, including their transcripts, firsthand. As a result of Monroy’s experience in admissions, he believes that grades tell only a small part of a student’s story.

“Academics are really fundamental, but they’re not the only piece of information that can let a college know if that student is a great fit for that school,” Monroy said. “A grade is just a subjective snapshot of how a student is doing in a certain subject in a given year based on not just the content that’s being taught, but also what’s going on in their lives outside of that.”

As a college counselor, Monroy tries to think holistically to get to know the full student rather than just their report card.

“Some of us are not mathematicians. Some of us have other things going on. Some of us need to take care of other things outside of school. There’s so many other factors that have to do with [college admissions],” Monroy said.

Despite the rationale, Metcalfe understands that sometimes this does not feel like the case for students, and the pressure for grades feels like it extends beyond college, even if that’s not necessarily true.

“People think ‘I have to have straight A’s to go to college,’” Metcalfe said. “And there’s some catastrophizing of, ‘If I get a lower grade, I’m not going to get into a good college. I’m not going to get into a good job. I’m not going to be a successful adult, and I’m going to be sad and alone,’ and being an adult, you look at that and say, ‘I promise it’s not that deep.’”